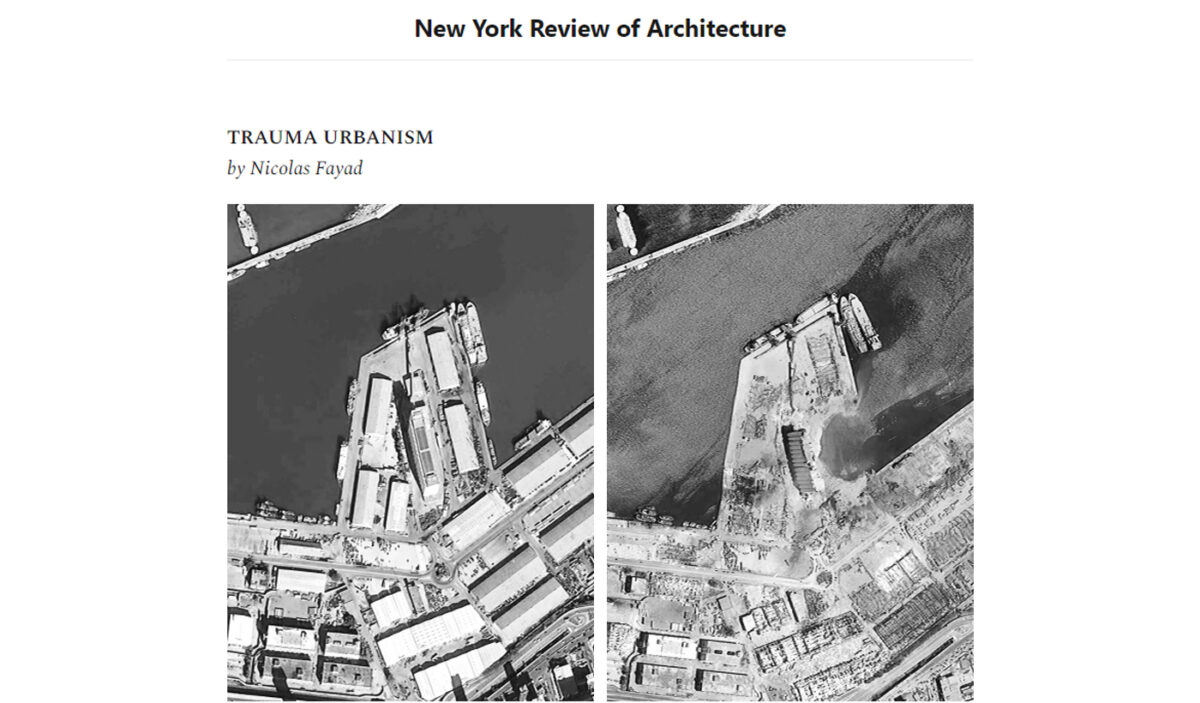

On August 4, 2020, a massive blast detonated at the Port of Beirut under a burning evening sun. Fifteen tons of fireworks, jugs of kerosene and acid, and thousands of tons of ammonium nitrate stored in a warehouse, coupled with a system of corruption and bribes, had let the perfect bomb sit unattended for years. In just a few seconds, the coup de grâce—which could be heard in Cyprus, about 145 miles away—dilapidated surrounding neighborhoods, leveling buildings, and reducing the urban fabric to hollow frames. Killing hundreds, injuring thousands, and leaving half a million homeless, the blast is considered one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history.

This unprecedented catastrophe, which left Beirut reeling, came at a time of extreme economic and political instability in Lebanon. Since post-civil war reconstruction of the city began in 1991, the Lebanese government has exhibited a blatant disregard for the city’s rich cultural heritage in favor of private interests. In 2013, for example, the construction of a luxury hotel and mall complex had already begun on one of the city’s most archaeologically significant sites before being halted due to pressure from activists.

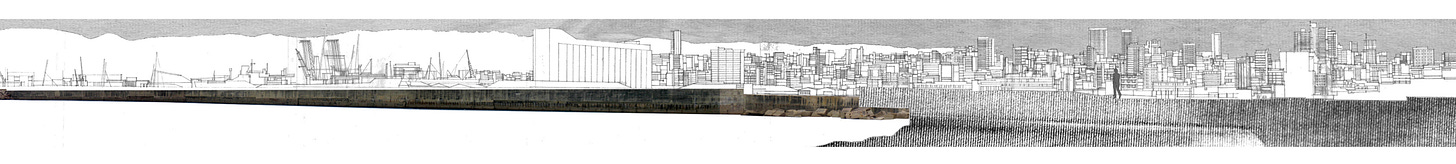

As Sandra Frem and Boulos Douaihy suggest in their exhibit for the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale, the government-owned port, which stretches for over one-third of Beirut’s coastline and serves as the main maritime entry point into Lebanon, is a physical manifestation of the state’s chronic dysfunction. For decades, it has been the backdrop of urban fracture, disconnecting and disfiguring the relationship of land and sea, haphazardly reshaping the interface between private and public. Years of unregulated private development along the water has turned the urban experience of Beirut’s coastline into isolated heterotopic landscapes: expansive stretches of reclaimed land, inaccessible and sometimes derelict. The reshaping of the natural coast over time has resulted in an archipelago of manmade landfills—a failed attempt at regenerating the city’s relationship to the Mediterranean Sea.

In order to identify the patterns and narratives of disruption, it is important to reflect on the city’s failed attempts at renewal over time. At the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975, Beirut, which had been transformed by the French Mandate in the aftermath of World War I and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, was a predominantly modern city with very few traces of its medieval past. The postwar reconstruction project of the 1990s constituted a second wave of modernization. Both rehabilitation efforts have successively erased Beirut’s history from the port, some of which dates back to the Phoenician era. In the early 1900s, the port ground was stretched to the east using debris of the medieval city to expand the cargo areas; a century later, the historical center of the port’s colonial quarters is being steadily replaced with high-rise buildings.

The latter reconstruction project has injected a sense of estrangement and alienation into the city’s downtown, encouraging retail therapy for a country that has never known nor come to terms with its past. Until the start of the civil war, the city center was a symbol of coexistence in Lebanon—a place where public space and social interaction were privileged. It is now a no man’s land for the elite. It appears that Beirut’s urban development has been driven by a state-sponsored cultural amnesia that promotes consumption as an indirect form of post-conflict reconciliation.

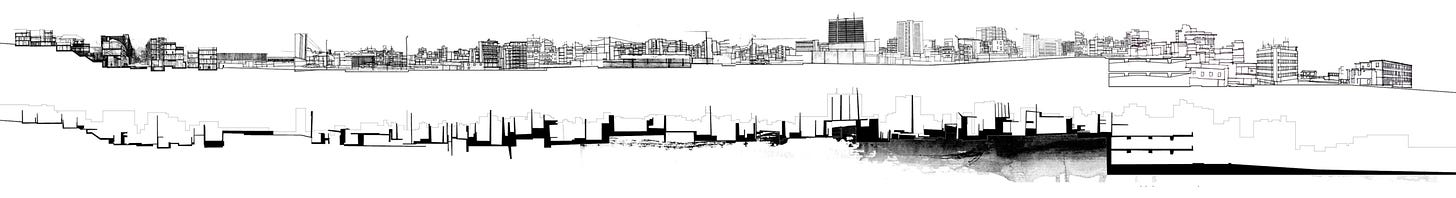

As the city has rebuilt itself over time, a pattern of trauma urbanism has become more apparent. In the aftermath of crises, rupture and obliteration have prevailed over transparency and inclusivity. Following last year’s explosion, Beirut is once again facing a restoration challenge, and it is in desperate need of stability and collective recovery. For architects, designers, and planners, the inextricable link between the port’s historical isolation and its recent destruction presents an opportunity to investigate new modes of negotiation between city, port, and surrounding enclaves. The effect of trauma on Beirut’s urban fabric provides context for addressing successive waves of conflict and catastrophes. But in order for this to be successful, it is crucial to confront the past.

So how do we recover the city while recognizing trauma in an attempt to reclaim Beirut’s forgotten past? Moving beyond the established history as presented and reproduced through spatial structures and everyday behavior, how can we imagine a new spatial contract for Beirut? To answer these questions, we must challenge the dominant reconstruction framework and redefine it as people-centered, socially just, and culturally sensitive. It is crucial to embrace recovery as a process that not only replenishes social and economic networks, but more importantly, prioritizes spaces of shared memories and social connection.

This spring at MIT, a group of students proposed solutions that do just this. Their interventions investigate the deployment of a new infrastructural ecology for a city that operates as an open system. The reimagined border space between Beirut and its port is conceived as a green armature, mediating the relationship between the existing urban fabric and the port’s operational networks.

As Beirutis face a new chapter, they must consider the balance between amnesia and nostalgia, remembering and rebuilding. If Beirut is to truly rise from its ashes, the reclamation of history must be central to urban planning efforts. Now is a time to imagine a new maritime facade for the city—one that allows the public to experience the water’s edge, and which acknowledges the vibrancies of the distant past, as well as the urgencies of an uncertain future.

NICOLAS FAYAD is an architect and educator, and co-founder of the Beirut-based East Architecture Studio. He is a senior lecturer at the American University of Beirut and a visiting lecturer at MIT.