Essay - Rethinking Pavilions as Potential Museums

“Rethinking Pavilions as Potential Museums” builds on a conversation that took place on May 9, 2025 between Nicolas Fayad, Lina Ghotmeh and Chris Dercon at the Fondation Cartier’s public program, hosted at the Fondazione Cini on the opening week of the 19th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale Di Venezia.

Rethinking Pavilions as Potential Museums

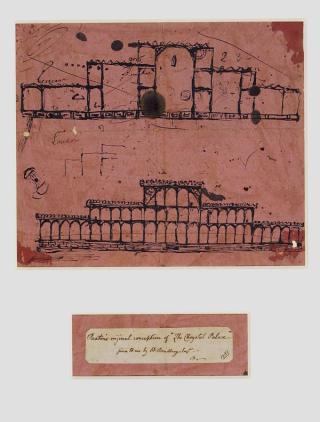

As architects we are often reinterpreting. We work carefully but without a pre-set plan or order. Instead, we dig into past assumptions, so to then show and preserve what we found. Following this thinking the Crystal Palace that was built in London for the Great Exhibition in 1851 is an early example that carries a great meaning when it comes to the legacy of pavilion architectures. The building had to be temporary, simple, as cheap as possible, and economical to build within the short time remaining before the exhibition opening. Conceived as a modular system of arched fragments, it was dismantled after the exhibition and relocated to an open area in South London. What makes it a pavilion, or more precisely a functional one is the mere fact of its adaptability and ability to move while still allowing the public to reclaim it, in this specific case, due to the smart systems that made it. For instance, it did not need artificial lighting to allow functions to inhabit, where natural light constantly diffuses through and from within interior spaces primarily enveloped by glass. Its adaptability was inherent to its making.

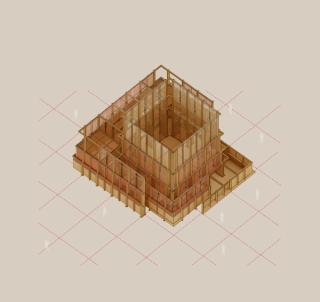

Paradoxically, and Chris as you mentioned a few days ago during one of our conversations, the Barcelona Pavilion which was dismantled in 1930 and recreated in the 1980s for example, other than serving the purpose of material innovation with the use of steel and glass at the time, has the tendency to erase its temporal adaptation. Except when in 2022, a minimal intervention forced to consider that question thanks to an installation that mimics, hugs and overlooks Mies’ masterwork but is made entirely of timber, reconsidering the modernist project that once promoted an innovation that might not be so relevant today, building on the fact that architecture cannot remain static and stable. The question that then comes to mind is; how can this exercise be as much about envisioning the future of pavilions as it is about conserving its past? I don’t necessarily have an answer to this question at the moment but what I realise is that pavilion architectures should aspire to be anticipatory - because we should be equally concerned with the future and its possibilities.

An Experiment in Preservation

I think there is a creative dimension to both our work which essentially operates under the banner of preservation, not necessarily in the field of conservation but more so when thinking that architecture has a profound role in preserving and expanding the cultural domain by simply listening to the contexts within which we work.

When I reflect on Lina’s Serpentine Pavilion, the Olga de Amaral exhibition, and our Musalla at the Islamic Arts Biennale, I see a profound resonance with the concept of scaffolding in architecture, both literally and metaphorically. These works reimagine and reengage with existing structures, not by treating them as new or isolated in the present, but through an intuitive excavation that uncovers layers of meaning and material. They merge the past with the present to create something emergent and alive. This process mirrors the practices that shaped these spaces, transforming them into what I envision as a kind of living museum or evolving collection of scaffoldings. In this sense, the scaffold becomes the enabler of occupation and transformation, the building itself takes on the role of scaffold, laid bare, revealing its core, and reclaiming its open-ended potential.

An Architecture of Scaffolding

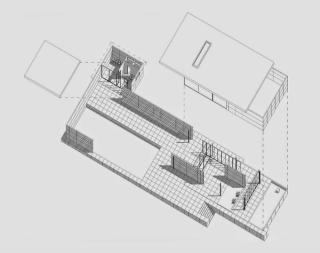

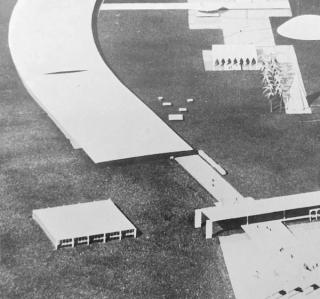

The relationship between the pavilion and its function takes me back to a project we completed a few years ago at the Tripoli Fair, originally designed by Oscar Niemeyer, never fully completed, nor ever functioned as a fair. We were asked to give new life to one of the 15 pavilions that make the Fair and inject a new program to what was intended to be used as a Guest House. Our intervention deliberately reveals and enhances the “DNA” that composes the structure. We insisted on conceptually preserving the expansive open plan that revolves around a central courtyard which is the primary source of light, around which revolves multiple programs. We had to imagine the programmatic use of the new space as ephemeral. Used as a design platform and prototyping facility for a few years, the Guest House could one day reclaim its original use, or another one altogether.

It is the notion of ephemerality, together with our desire to keep the structure intact, that made our intervention reversible: the lightweight partitions, lighting fixtures, and machinery could be removed, leaving space for another programme to take over, yet with the integrity of the original design still untouched. Abstract like the Fair, the intervention would feel as if nothing had been done, or as if it had always been present.

Maybe one of the most satisfying things in these types projects is our ability to learn a different language that is external to us, that come with a level of modesty that speaks to history and to imagines a space that preceded us by decades and will continue to live in a different shape and form. So essentially, function might not be the guiding principle when conceiving of pavilion architectures, but mostly the making of it, to allow for multiplicity of scenarios to unfold from within it in different temporal and contextual conditions.

Pavilions and their Temporality

More recently, I’ve come to understand that the act of building embodies restitution as a creative process, one that goes beyond nostalgia or the pursuit of origins and authenticity. This shift in perspective is essential for moving beyond the existing into the realm of the imagined. What we call “new” is often interwoven with what came before, much like a scaffold, anchored in local craft and practices, yet open to future uses and interpretations.

This becomes even more relevant in the context of temporary structures or exhibitions, such as Biennales and Fairgrounds, where the intangible nature of the museum space transforms into an experimental ground. While these events leave behind fewer physical remnants, they paradoxically open up greater possibilities for future action. The temporary becomes a fertile framework, scaffold in the most literal sense, through which we can expand the scope of what a museum can be. Adaptability and transience, rather than diminishing the value of these structures, become the very tools for reimagining the institution’s reach and role.

Returning to the idea of the fragment, it is not something perceived as ‘new,’ but rather as part of an ongoing, experimental process of making. It represents an act of reconstructing the past, one that embraces its layered histories with all their complexities, aspirations, and truths. This process invites us to participate in the everyday work of shaping the world we’ve inherited, fostering a space where cultural continuity can thrive and co-authorship can emerge, particularly in the dialogue between traditional craftsmanship and contemporary construction techniques.

In this context, the architecture of scaffolding becomes more than a structural metaphor; it becomes a space of humility, learning, and the exchange of knowledge. It reflects an evolving practice where building is not about erasing or replacing, but about engaging, reinterpreting, and collaborating, where the past is not static, but active in shaping the future.

Rather than positioning the past and future as opposing conditions, one might instead approach them through the framework of an intellectual craft: a process in which existing elements are elevated through precise and intentional acts of detailing. Within this context, engaging with local trades becomes a mode of mediation, one in which design methodologies are enriched by adopting the sensibility and mindset of the artisan.

This collaboration forms a productive site of knowledge exchange. The architect, working within known standards and conventions, subtly alters construction techniques to propose new outcomes, while the artisan extends their practice into unfamiliar contexts, reinterpreting it within a different cultural and spatial framework. Such interactions create a dynamic field of reciprocity, where both parties contribute to a process that is simultaneously rooted in tradition and open to innovation. The act of engaging with history in this way, and of envisioning spaces that transcend linear time, offers a deeply meaningful creative experience. It fosters a continuity that is neither nostalgic nor reductive, but generative: a sustained dialogue between past, present, and future that is essential to the evolving language of architecture and craft.